William Morris, the Soul of Arts and Crafts

Tiles from Textiles Arts & Crafts Pre-Raphaelite Victorian Medieval

Tiles from Textiles Arts & Crafts Pre-Raphaelite Victorian Medieval

The Forest, 1887, William Morris,Philip Webb, John Henry Dearle, Merton Abbey Workshop (see tiles)

The forest is not a quiet place in the summer. Small birds roar together, the coded sounds of squirrels tapping their little feet resonate, and the screeches from the occasional colony of peacocks would travel for a mile. Leaves rustle as deer pass through a clearing. Eyes follow visitors from the shadows. Add to this a pony and a proper suit of armor and you can imagine the world through the eyes of an eight-year-old.

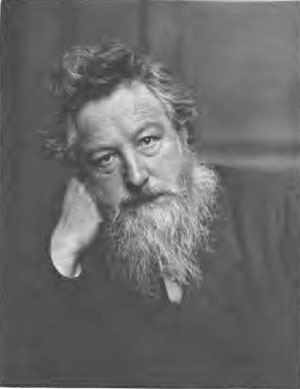

Such a boy was William Morris. By 1842, his family had moved to Woodland Hall, a large Georgian home in Walthamstow, then a country village outside London. William was only six when his family moved to the large Woodland Hall at the edge of Epping Forest, his father having profited from wise investments. In an area more remote than it is now, he spent summer days spent exploring every unfurled fern and native birds in the forest, as well as the old Essex churches in the area. Winter days were spent reading Chaucer and tales of Arthurian legend.

The solidly middle class Morris family was now clearly nouveau riche but with strong religious values; the elder Morris himself was an Evangelical and his household was strictly run despite the indulgences he lavished on his eldest son. Although William had his eight siblings, two older sisters, and the rest younger, he was a bookish and solitary child.

There would be no adolescent rebellion against his father's ideas for Morris. When William was 13, his childhood came to an end. His father died suddenly and the family moved to a more modest home, Water House. Shortly thereafter, William was sent off to Marlborough College, a rough public school. Morris later wrote that he had learnt nothing there. What he did learn at Marlborough was how to communicate to members of other social classes, an ability that would serve him in good stead later. He also turned from the Evangelicism of his family in favor of Anglo-Catholicism, a strong movement within the Church of England that called for moral seriousness and a return to ritual and ceremony and faith through works of service. When riots broke out at Marlborough, he returned home and was homeschooled until he left for Exeter College at Oxford, where he planned a career as Anglo-Catholic clergy.

Nineteenth century Oxford was a masculine stronghold wherein the ghosts of great men walked the halls with its current students. By mid-century, the "Oxford Movement" had permeated undergraduate life with a distinctly spiritual flavor: The Church is a divinely ordained and ordered society intended to transcend politics, geography, and time. The experience of such a society changes how we think about spiritual matters. It was, in essence, a theological romantic rebellion against the rationalism of the Enlightenment that had taken hold in the Church of England.

Within a few days of his arrival, Morris met and befriended Edward Burne-Jones, who was to remain his closest life-long friend. Burne-Jones also introduced him to Charles Faulkner, who would be a founding member of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co. ('The Firm'). Morris, Burne-Jones, and Faulkner and their associates intended lives as clergy, often debating theology and literature until dawn. Burne-Jones and Morris studied the medieval illuminated manuscripts at the Bodleian Library, becoming increasingly of the opinion that the Middle Ages church-centered communities offered a model a better model of social organization than industrialized England. At the time, Morris intended to use his inheritance to found a monastery on this model.

In the summer of 1855, the two friends became interested in John Ruskin, whose works introduced him to the PreRaphaelites. They sought out works by Millais and Rossetti. Stunned by Rossetti's drawing of the head of Beatrice, the found the authenticity and direction in life hat they had looked for in religion. On a tour of Gothic architecture in northern France with Burne-Jones in 1855, the die was cast: The two abandoned their intentions to take Holy Orders and resolved to dedicate themselves to a life of art, Burne-Jones to painting, and Morris to architecture.

It is difficult to overestimate the impact of the Gothic Revival in architecture, not only on Morris and Burne-Jones, but on the age. The Gothic Revival architectural movement began in the 1740s but by the mid-nineteenth century was so intertwined with the Oxford Movement's call to renewed spirituality that the forms of buildings presented a visual tableau of the reactionary response to industrialization. The architect Pugin (Contrasts, 1836), widened the compass of medieval art and architecture to include the whole medieval ethos, asserting that Gothic architecture was born of a purer society. Ruskin's Nature of the Gothic whipped this wildfire notion to a frenzy that spread throughout Europe, Australia and the Americas well into the twentieth century, such that the eventual number of Gothic Revival structures matched or exceeded the number of authentic Gothic structures built between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries.

In such a frenzy did the two friends return to Oxford. Morris left Exeter College as soon as possible with a Pass degree and Burne-Jones abandoned his education with a single term remaining. Morris took up an apprenticeship with George Edmund Street, a Gothic revival architect and Burne-Jones left for London. Morris found work as an apprentice tedious and stayed only three months, but while at GE Street, he made the acquaintance of Philip Webb. Webb would later design Red House, first married home with Jane Burden Morris and a creative center for Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and other friends. Philip Webb would also go on to create many of the Morris & Co. designs.

During this time, Morris made his first venture into publishing, The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine wherein he published his and others' works, including eight romances, much of his undergraduate poetry, and an article on the Amiens cathedral. As with the later Kelmscott press, the style as well as many of these works drew their inspiration from medieval themes.

In 1856, Morris moved in with Burne-Jones in modest quarters in London. Burne-Jones had managed to meet Rossetti, arguably the driving force behind the first wave of PreRaphaelite art. Rossetti's work had by now moved from painting from nature to medieval and chivalric themes, themes that resonated with Morris's own internal harmony. Rossetti persuaded Morris to abandon architecture in favor of painting. Morris's painting career was brief and unsuccessful by his own standards. He never mastered drawing the human figure and in the Morris & Co. years would have Philip Webb, Burne-Jones, Rossetti or others complete these parts of his designs. He continued to focus on medieval themes in clay modeling, carving in wood and stone, and illuminating books, as well as painting.

Oxford Union Murals

Not long thereafter, an exciting thing happened: Rossetti arranged to have a group of young artists paint murals on the Oxford Union Society's Debating Hall. Morris, Burne-Jones, Val Prinsep, Arthur Hughes, John Hungerford Pollen, and Roddam Spencer-Stanhope joined Rossetti. Working for only living expenses, the group painted scenes from Le Morte D'Arthur. Sadly, the walls were poorly prepared to receive the paint and the brilliantly colored works began to disappear almost immediately. That the murals degenerated quickly due to poor preparation and materials was not lost on Morris and a detailed attention to the quality of materials used became a hallmark of all his later creative endeavors.

Left: Elizabeth Siddal, 1855, pen and ink drawing by Rossetti

Right: Photograph of Jane Burden at age 19, 1858, a year before her marriage

to William Morris

Two women stood at the center of Preraphaelite beauty: Lizzie Siddal, a poet and artist who received a subsidy from John Ruskin as an encouragement to her work, and Jane Burden Morris. Lizzie's beauty was characteristic of the "first wave" of Preraphaelite art: pale, holy, and otherworldly (For example, Millais, The Bridesmaid, 1851; Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini, 1850). At the time, many women died after taking toxic potions to achieve a chalky looking complexion. "Fowlers Solution", used to "revitalize" aging skin, contained arsenic. Jane Morris's darkness, her tall, slender figure, her melanchoic expression, and choice of dark flowing gowns over crinolines was more characteristic of the "second wave", whose women could also be dark, disobedient, (like Rossetti's Pandora, 1869), evil (like Burne-Jones's Sidonia, 1860), or mad (like Hunt's Lady of Shallot, 1905).

Rossetti had a reputation, overstated but not undeserved, of being a womanizer. One evening in 1857, he and Burne-Jones were attending the theatre when he spotted a beautiful young woman, tall with dark hair, and was immediately drawn to her. She was Jane Burden, the daughter of a stable hand, and attending the theatre with her sister, Bessie. Rossetti persisted in his attempts to have her model for him and she eventually agreed. Jane sat for the single Morris painting that remains, La Belle Iseult. While he was working on La Belle Iseult, he fell in love with Jane, and inscribed the back of the canvas with "I cannot paint you, but I love you."

Left: Early painting, Aphrodite Rising out of the Sea.

By 1862, Morris had abandoned painting.

Right: La Belle Iseult, William Morris, Jane Morris, model.

Morris inscribed on the back,

such that she could see it

as she modeled, "I cannot paint you, but I love you."

Although his friends laughed at the awkward courtship attempts of the burley "Topsy", Jane eventually did agree to marry Morris and they were married on 26 April 1859. While Morris and the PreRaphaelites had no problem with mixing with people of the lower classes, Morris's family did not share those ideals. William had disappointed the family with the apprenticeship at GE Street and by 1859, no one from Morris's family attended his wedding. It was not until the birth of Morris's oldest daughter, Jenny, in 1862 that relations became more cordial with the elder Mrs. Morris.

Rossetti was still enamored of Jane, but in a long-term relationship with poet and artist, Lizzie Siddal, whom he married the year after William and Jane were wed. After Lizzie's death, Rossetti's attraction to Jane turned to obsession and she became his muse. This relationship continued and deepened for many years.

Red House was the first married home of the Morrises but what beautiful nest-building! Designed for Morris by Philip Webb, whom he'd met during his apprenticeship for G.E. Street, Morris took an active part in every aspect of the home's construction. Red House was unique for its time on many counts. Webb designed Red House in a Tudor - Gothic style, not a popular style of the times. Tudor style had gone out of style 80 years before, and the medieval red brick of other heritage Tudor estates, such as Althorp, the home of Princess Diana, were being covered in brick tile or additional layers of gray brick.

For the most part, the decoration of Red House was a communal effort, with Burne-Jones painting scenes on the walls, and Lizzie Siddal, Georgina Macdonald, and Jane implementing the needlework designs of Morris. By 1860 Rossetti had married Lizzie Siddall and Burne-Jones, Georgina. Weekends provided an artistic retreat and a group of artist friends became regular visitors. In addition to the Rossettis and the Burne-Joneses, Charles Faulkner and his sisters, Philip Webb, the poet Swinburne were frequent visitors. In the years that followed, Lizzie Siddal lost a child and overdosed on laudanum while pregnant the next year. The coroner ruled it an accident but there was talk.

Jane was intelligent, if uneducated, and eventually learned both French and Italian. She was a voracious reader, and successfully managed the large household at Red House, serving as hostess to its many visitors. Jane bore two daughters: Jenny and May, in 1861 and 1862, respectively. She was, by all reports, a melancholic, private person whose main concern was the welfare of her children.

The decoration of Red House, its walls, and furnture was an ongoing labor of love for Morris and his circle. It was only natural that it should grow into something larger.

St. George cabinet, Red House,

William Morris and Philip Webb

It was during an evening dinner at at Red House in 1861 that, almost as a joke, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, & Co. was born. It was agreed that each member of the group should put in some money and a firm would be started to create decorations and furniture as it had been in olden days. 'The Firm', as it came to be called, included: Morris, Rossetti, Charles Faulkner, Ford Maddox Brown, Philip Webb, and Marshall, an accountant friend of Ford Maddox Brown.

Among The Firm's first products were tiles, designed by Morris in botanical patterns or by Burne-Jones on medieval, mythic, and fairy tale themes. This moved naturally into stained glass and many of the designs for tile were implemented as stained glass as well as vice versa. The growth of Anglo-Catholicism had born a return to ritual, and evocative church adornment and churches began to add stained glass windows, tiles, and furnishing in religious motifs. Soon, the majority of The Firm's business was ecclesiastical.

The Ruskin influence on Morris remained strong and the mission of The Firm became one of restoring the soul to goods that had been degraded by mass-production and industrialization. Ruskin, and Morris, held that perfectly finished goods made by machines were spiritually inferior to their imperfect counterparts made by craftsmen. Medieval Christian themes, and depictions of fairy tales wherein a good heart triumphs over evil, as well as the beauty of the natural world became the mainstays of The Firm's offerings.

Morris wrote around this time that he did not like wallpaper; he thought it an inferior replacement for the handiwork of the rich tapestries he loved. As a child, Morris had seen a tapestry hanging in Queen Elizabeth's Lodge in Epping Forest, "a room hung with faded greenery" that had evoked his childhood imagination. Tapestries, however, embodied the artistic conflict at the center of Morris's endeavors: They were work intensive and beyond the budget of the working classes to whom he wanted to restore the spiritual world through art.

Attainment of the Holy Grail tapestry designed by

Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co., 1895-1896

Morris came to design wallpapers based on botanicals that he recalled from his days in Epping Forest as well as the gardens at Red House. Unfortunately, very few of his first designs sold well and he did not return to wallpaper design for several years.

The production of wallpaper, and then silks, chintz fabric, and carpet was an exception to Morris's commitment to having the designs of the Firm produced in-house. Morris was not opposed to using machinery if it could spare the worker tedious hours, and these products were often farmed out. William De Morgan had originally created designs for glass and tiles in house; eventually, he started his own pottery company and most of The Firm's tiles were produced by him.

The Firm's furniture was of two sorts, both designed primarily by Philip Webb, at first with Morris's input and direction. The first, heavily carved in a medieval style, and designed to be painted, is that we characterize as English Arts and Crafts, and was the style created for Red House. The other, with simpler clean lines was more easily produced in quantity and, being cheaper, remained in production for several decades.

Morris's creative activities afforded him little time to focus on sound business practices. By 1865, The Firm's finances were in disrepair and at the same time, the Morrises expecting their second child. Morris and Burne-Jones made plans to add a new wing to Red House for Edward, Georgina and family, but first young Philip fell ill with scarlet fever, and then the pregnant Georgina. Their second son, Christopher, died three weeks after his birth and when Georegina fell into a depression, the plans were abandoned. This was a great disappointment to Morris, himself ill with rheumatic fever, on both financial and emotional levels. A business decision was made for the Morrises to leave Red House and take up quarters over the shop in London. The Burne-Jones murals and the heavier furniture could not be moved and it grieved Morris greatly. It was an end of an era.

The move to London also signaled the end of Morris's marriage in all but name. Rossetti had never ceased to be enamored of Jane and after Lizzie's death, he became obsessed with her. Now his feeling were reciprocated. Morris wrings of this time, such as The Earthly Paradise, stories that are poignant and tragic, nearly autobiographical. He was an impatient man and given to rages, perhaps pushing Jane into Rossetti's arms. As her love for Rossetti grew apparent to everyone, Morris never wavered in his love for her, even sharing quarters with Rossetti in order to forestall further damage to her reputation. He renewed his focus on his work, and summered in Iceland in 1869, leaving his wife in the arms of Rossetti while he translated the Eddas he would publish in the next two years. Both the landscape and culture of Iceland impressed him and he returned renewed.

Kelmscott

Manor, painting by May Morris

Morris leased Kelmscott Manor, an Elizabethan manor built near the banks of the Thames, with Rossetti and the two men shared the quarters with the Morris family. This was undoubtedly done in an effort to salvage what was left of Jane's reputation as Rossetti had been anything but discreet -- feeding her strawberries at parties and sitting sideways to focus on her even, or especially, when Morris was present. Until 1874, when Rossetti quit the home, Morris did not spend much time there. Rossetti had attempted suicide in 1872 and Jane broke off the affair with him over concerns for the affect he might have on her children. She continued to correspond with him until his death a decade later. With Rossetti gone, Morris returned to Kelmscott Manor and began to feel at home in his home. He wrote his utopian novel, News from Nowhere, and allowed himself the leisure of fishing and exploring the countryside as he had in Epping Forest as a boy.

Morris never changed residences again. After his death, his daughter May was able to arrange Kelmscott Manor's purchase by her mother. Jane lived there until her death in 1914.

In 1875, Rossetti and Morris dissolved their business partnership, more amiably than might be expected. The original members of The Firm being long absent, the new firm was reorganized around Morris's direction and was known simply as Morris & Co.

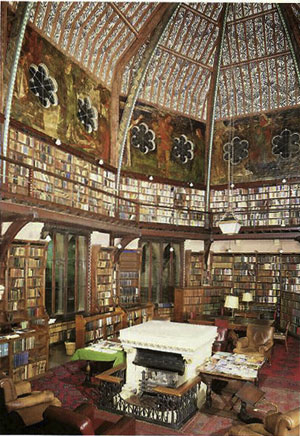

Since its inception, The Firm's focus had shifted from ecclesiastic products toward home decoration and domestic products. Morris appears to have overcome his ambivalence to wallpaper, producing 19 new designs within the next few years. Many were implemented both as wallpaper and textiles. The new designs carried a suggestion of medieval and oriental influences and were much better received by the public than his original designs. Morris disliked the synthetic aniline dyes that were commonly used and began experimenting with natural dyes for his textiles. Kelmscott House was large and afforded Morris the room to design and weave his own tapestries and carpets. But the addition of the tapestries and carpets to The Firm's offerings warranted a move to larger quarters, Merton Abbey on the banks of the River Wandle.

Textile printing at Merton Abbey

At the same time, Morris's oldest daughter began having seizures and was diagnosed with epilepsy. It was concluded that the condition was hereditary and from Morris's side of the family. In spite of the hearbreaks in his personal life and the demands of the firm, Morris produced two new translations during this time.

At the same time that Morris was producing expensive goods affordable only by the rich, his attention was turning increasingly to public affairs and the concerns of the working classes, at first coming out against war with Russia. He was a founding member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, asserting that the degraded state of art was a reflection of the degraded state of the common workman and hoped to elevate the working classes through art. He read extensively and in 1883, he became a socialist. He went on the lecture extensively, attending rallies indoors and outdoors, in fair and inclement weather, even once getting arrested. He believed that a revolution was inevitable and remained very active in the movement until he fell ill in 1891.

His health now requiring careful monitoring, Morris re-evaluated his activities and soon the less physically taxing Kelmscott Press was born. Morris had from early on had an interest in illuminated manuscripts and early printed books. Soon he was researching all facets of book publishing.

Morris designed three type fonts: Golden, Troy, and Chaucer. The books were vellum-bound and illustrated designed by Burne-Jones and cut as wood-blocks by Morris himself. Kelmscott Press produced only 53 titles and never made a profit. It ceased operation in 1898, two years after Morris's death from diabetes, but was influential as a forerunner to the revival of private presses in Britain and the states and the advent of "gift books" during the Golden Era of Illustration that was to follow.

Following Morris's death in 1896, Morris & Co. continued. John Henry Dearle a 30+ year Firm veteran who had started working for The Firm in his teens, became Art Director. When Burne-Jones died in 1898, Dearle became its principal stained glass designer. Many of his early designs was sold under Morris's name. His later work show distinct Persian and Turkish influences, although he maintained a strong commitment to Morris's aesthetic values. May Morris continued as Director of Embroidery.

Left: Screen designed and embroidered by May Morris

An almost religious quality characterizes the dense and elongated patterns drawn from nature, and mythic figures of saints and heroes. Pure colors, exposed materials and an organic manner inform homes that are woven into the tapestry of their surroundings. Early arts and crafts interiors even seem cluttered by modern standards. Absent are pretension, clutter and the lavish trimmings of the Victorian era. More than a century since his death, Arts and Crafts styles and values have made their way to every continent. Morris's central conflicts remain unresolved: Costly artisan work vs. availability; rich carvings, inlays and tapestries vs. simple lines and natural materials; a reactionary posture against soulless industrialization vs. freeing workers from the tyrrany of tedious and repetitive tasks. That dialectic continues to this day, but there can be no doubt of Morris's influence on the philosophy of modern design. His aesthetic has taken on a life of its own, burning away the inessential, the dross of acquisitiveness, reveals what is truly "beautiful or useful".

~XineAnn

red house pilgrim's rest garden porch tiles

tiles from textiles (overview)

morris & co tiles from textiles

birds and betrayal, a trip to iceland

william demorgan arts and crafts overview

de morgan arts and crafts tiles

medieval, maps and bestiary tiles

victorian era tiles - what is victorian?

William Morris Tile • Site Map • Catalog • How to Order Tile • Privacy Statement • Contact

Copyright information: Images of tile products on this website are ©William Morris Tile, LLC. They are derivative works requiring considerable creative effort. You are welcome to use the images, with attribution, for any non-commercial purpose, including displaying them on your blog or personal website. You may not use them for any commercial purpose without written permission, including but not limited to creating counted cross-stitch patterns, calendars, or any other commercial purpose. Contact me for images.